import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

sns.set_style("whitegrid")

np.set_printoptions(precision = 3)

pd.set_option('display.precision', 3)

url = "https://github.com/propublica/compas-analysis/raw/master/compas-scores-two-years.csv"

compas = pd.read_csv(url)8 Bias and Fairness in Automated Decision Systems

The COMPAS Investigation

Open the live notebook in Google Colab or download the live notebook.

Today we are going to study an extremely famous investigation into algorithmic decision-making in the sphere of criminal justice by Angwin et al. (2022), originally written for ProPublica in 2016. This investigation significantly accelerated the pace of research into bias and fairness in machine learning, due in combination to its simple message and publicly-available data.

In 2016, ProPublica published on article called “Machine Bias”. The subtitle of this article offered a simple claim:

There’s software used across the country to predict future criminals. And it’s biased against blacks.

The software that the ProPublica authors studied is called the “Correctional Offender Management Profiling for Alternative Sanctions,” or COMPAS, produced by the company Northpointe. COMPAS begins with a survey administered to a person involved with the criminal justice system (such as a defendant or inmate). The survey includes a wide range of questions about a defendant’s demographics, personal history, environment, and criminal record. From these survey inputs, the COMPAS algorithm computes a risk score that the person in question would recidivate (commit another crime) in the next two years. This risk score can be used by courts to make decisions about whether a defendant should be released on bail prior to a hearing, or whether a current inmate should be considered for parole.

In the context of classification, we can think of the COMPAS algorithm as a predictive classifier with labels 0: Will not recidivate and 1: will recidivate.

In these notes, we’ll introduce the topic of how to assess whether a classifier like this one is fair or biased. We’ll reproduce some of the main findings of the ProPublica article, as well as findings from subsequent analyses which challenge the ProPublica claims.

Getting To Know The Data

Although we won’t use most of the detail from the COMPAS data collection survey, it’s helpful to get a sense of what kinds of information are collected about defendants. Here’s a sample form used for feature collection in the COMPAS risk assessment.

What do you notice in the COMPAS sample form? Are there kinds of information collected that concern you in the context of predictive recommendations that may impact a person’s freedom?

Data Acquisition and Preparation

Now let’s download the COMPAS data set published by ProPublica. This data set was obtained by Angwin et al. (2022) through a public records request. The data comprises two years worth of COMPAS scoring in Broward County, Florida.

This data set contains python {len(compas)} rows and python {len(compas.columns)} columns. Each row corresponds to a defendant who was scored by the COMPAS algorithm, and each column corresponds to a different feature collected about that defendant. For our analysis we’ll only need four of the feature columns:

cols = ["sex", "race", "decile_score", "two_year_recid"]

compas = compas[cols]

compas.head()| sex | race | decile_score | two_year_recid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Male | Other | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | Male | African-American | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | Male | African-American | 4 | 1 |

| 3 | Male | African-American | 8 | 0 |

| 4 | Male | Other | 1 | 0 |

The decile_score column contains the risk score assigned by the COMPAS algorithm, which ranges from 1 (lowest risk) to 10 (highest risk). The two_year_recid column indicates whether the defendant was in fact charged with another crime within two years of their initial scoring (1 = yes, 0 = no). We can think of the decile_score column as a prediction made by the COMPAS algorithm, and the two_year_recid column as the ground-truth label that COMPAS is trying to predict.

Following ProPublica, we are going to restrict our attention to white (Caucasian) and Black (African-American) defendants:

is_white = compas["race"] == "Caucasian"

is_black = compas["race"] == "African-American"

compas = compas[is_white | is_black]

compas = compas.copy()Our data now looks like this:

compas.head()| sex | race | decile_score | two_year_recid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Male | African-American | 3 | 1 |

| 2 | Male | African-American | 4 | 1 |

| 3 | Male | African-American | 8 | 0 |

| 6 | Male | Caucasian | 6 | 1 |

| 8 | Female | Caucasian | 1 | 0 |

Preliminary Explorations

Let’s do some quick exploration of our data. How many defendants are present in this data of each sex?

compas.groupby("sex").size()sex

Female 1219

Male 4931

dtype: int64What about race?

compas.groupby("race").size()race

African-American 3696

Caucasian 2454

dtype: int64The decile score is the algorithm’s prediction. Higher decile scores indicate that, according to the COMPAS model, the defendant has higher likelihood to be charged with a crime within the next two years. It’s worth emphasizing that this isn’t the same thing as committing a crime: whether or not you’re charged also depends on the behavior of police and prosecutors, which are known to often display racial bias.

In the framework we’ve developed in this class, you can think of the decile score as being produced by computing a score like \(s = \sum_{i = 1}^p w_i x_i \rangle\) for each defendant, and then dividing these into the lowest 10% (decile score 1), the next 10% (decile score 2), the next 10% (decile score 3) and so on. The weights in the model would need to be computed using a training algorithm like logistic regression.

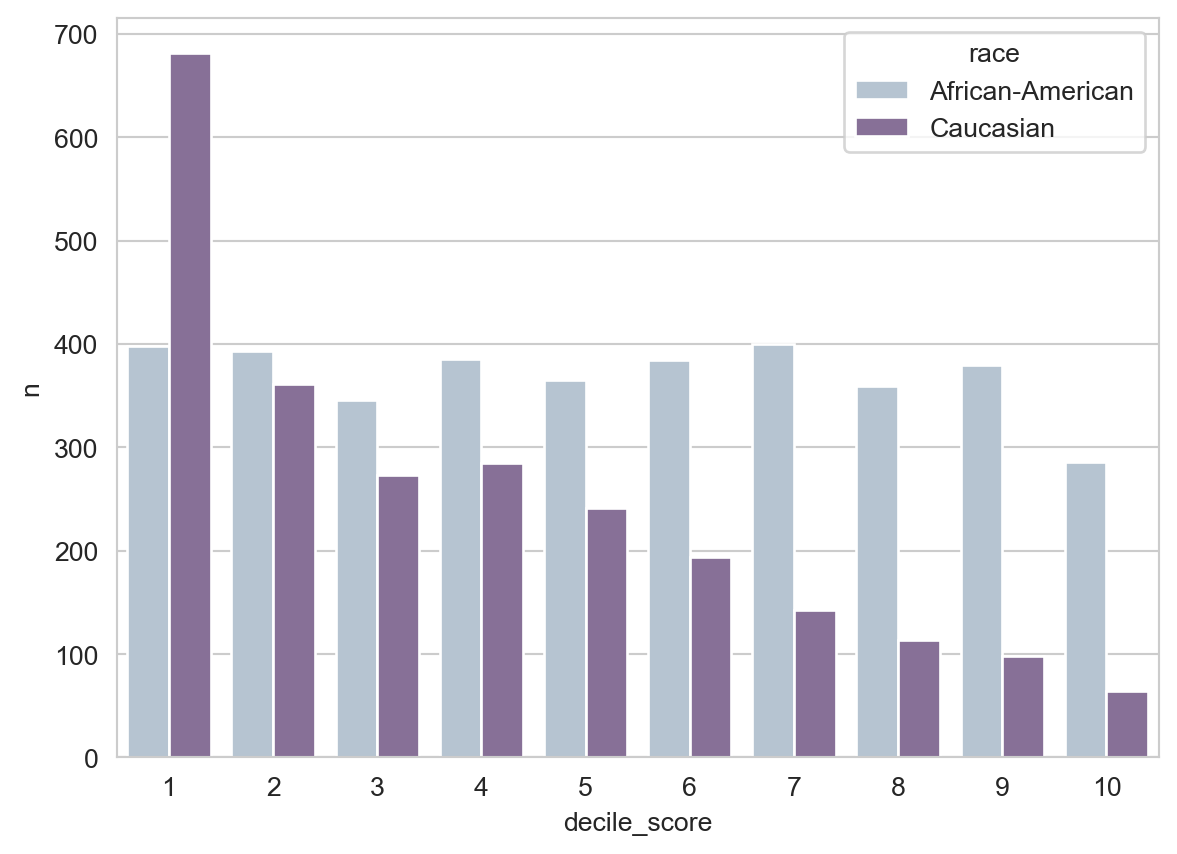

Let’s take a look at the decile scores assigned to defendants in this data by the COMPAS algorithm:

counts = compas.groupby(["race", "decile_score"]).size().reset_index(name = "n")

p = sns.barplot(data = counts,

x = "decile_score",

y = "n",

hue = "race",

palette = "BuPu",

saturation = 0.5)

You may notice that the number of white defendants who receive a given decile score tends to decrease as the score increases, whereas the number of Black defendants remains relatively constant. This is our first hint that Black defendants may tend to receive higher risk scores than white defendants.

Let’s also take a look at the recidivism rate in the data:

compas["two_year_recid"].mean()np.float64(0.4661788617886179)So, in these data, approximately 47% of all defendants went on to be charged of another crime within the next two years. This is sometimes called the prevalence of the outcome. Although this is not a “good” outcome, it is labeled 1 in the target data and so we refer to this as the “positive” outcome. Prevalence without further specification usually refers to prevalence of the positive outcome.

The base rate of prediction accuracy in this problem is 53%: if we always guessed that the defendant was not arrested within two years, we would be right 53% of the time.

We can also compute the prevalence broken down by race of the defendant:

compas.groupby("race")["two_year_recid"].mean()race

African-American 0.514

Caucasian 0.394

Name: two_year_recid, dtype: float64The prevalence of recidivism is approximately 39% for white defendants and 51% for Black defendants. This difference will have major consequences later on for the possibility of different kinds of fairness in classifiers.

When interpreting these different prevalences, it is important to remember that

- The relation between arrest/charging and actual criminal offense can display racial bias, with effects varying by geography (Fogliato et al. 2021).

- Race is itself a socially-constructed system of human categorization invented by humans with political and economic motives to describe other humans as property (Bonilla-Silva 2018).

- Decisions about which behaviors are criminal are contingent political decisions which have, historically, fallen hardest on Black Americans (Yusef and Yusef 2017).

We’re going to treat the COMPAS algorithm as a binary classifier, but you might notice a problem: the algorithm’s prediction is the decile_score column, which is not actually a 0-1 label. Following a common usage of the algorithm in application settings, and the analysis by ProPublica, we are going to construct a new binary column in which we say that a defendant is predicted_high_risk if their decile_score is larger than 4.

compas["predicted_high_risk"] = (compas["decile_score"] > 4)Now that we’ve done that, we can ask: how likely are Black and white defendants to receive positive predictions in this data?

compas.groupby("race")[["two_year_recid", "predicted_high_risk"]].mean()| two_year_recid | predicted_high_risk | |

|---|---|---|

| race | ||

| African-American | 0.514 | 0.588 |

| Caucasian | 0.394 | 0.348 |

Black defendants are substantially more likely to receive a positive prediction than white defendants, and the disparity is larger than the observed prevalence of the positive outcome.

Is this fair? What is your gut telling you? Yes, no, possibly? What information would you need in order to make a judgment? What is the principle on which your judgment rests?

The ProPublica Findings

Let’s now ask a few questions about the the predictive accuracy of this algorithm. First, how accurate it is it overall?

compas["correct_prediction"] = (compas["predicted_high_risk"] == compas["two_year_recid"])

compas["correct_prediction"].mean()np.float64(0.6508943089430894)Recall that the base rate in this problem is 53%, so our accuracy is somewhat better than random guessing.

What about the accuracy on Black and white defendants separately?

compas.groupby(["race"])["correct_prediction"].mean()race

African-American 0.638

Caucasian 0.670

Name: correct_prediction, dtype: float64The overall accuracies for Black and white defendants are comparable, and both are somewhat higher than the base rate of 53%.

What about the error rates? Here is a simple calculation which computes the false positive rate (FPR) in the first row and the true positive rate (TPR) on the bottom row:

compas.groupby(["two_year_recid"])["predicted_high_risk"].mean().reset_index()| two_year_recid | predicted_high_risk | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0.352 |

| 1 | 1 | 0.654 |

However, and this was the main finding of the ProPublica study, the FPR and FNR are very different when we break down the data by race:

compas.groupby(["two_year_recid", "race"])["predicted_high_risk"].mean().reset_index()| two_year_recid | race | predicted_high_risk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | African-American | 0.448 |

| 1 | 0 | Caucasian | 0.235 |

| 2 | 1 | African-American | 0.720 |

| 3 | 1 | Caucasian | 0.523 |

The false positive rate for Black defendants is much higher than the false positive rate for white defendants. This was the main finding of Angwin et al. (2022). The FPR of 45% for Black defendants means that, out of every 100 Black defendants who in fact will not be charged with another crime, the algorithm nevertheless predicts that 45 of them will. In contrast, the FPR of 24% for white defendants indicates that only 24 out of 100 non-recidivating white defendants would be predicted to be charged with another crime.

There are a few ways in which we can think of this result as reflecting bias:

- The algorithm has learned an implicit pattern wherein Black defendants are intrinsically more “criminal” than white defendants, even among people who factually were not charged again within teh time window. This is a bias in the patterns that the algorithm has learned in order to formulate its predictions. This is related to the idea of representational bias, in which algorithms learn and reproduce toxic stereotypes about certain groups of people.

- Regardless of how the algorithm forms its predictions, the impact of the algorithm being used in the penal system is that more Black defendants will be classified as high-risk, resulting in more denials of parole, bail, early release, or other forms of freedom from the penal system. So, the algorithm has disparate impact on people. This is sometimes called allocative or distributional bias: bias in how resources or opportunities (in this case, freedom) are allocated or distributed between groups.

We can think about the argument of Angwin et al. (2022) as a two-step argument:

- The COMPAS algorithm has disparate error rates by race.

- Therefore, the COMPAS algorithm is unjustly biased with respect to race.

This argument implicitly endorses the following requirements of fairness:

A necessary condition for an automated decision system to be (approximately) fair is that it have equal (approximately) rates of false positives and false negatives across identity groups.

This principle is sometimes called error rate parity.

The Rebuttal

Angwin et al. (2022) kicked off a vigorous discussion about what it means for an algorithm to fair and how to measure deviations from bias. In particular, Northpointe, the company that developed COMPAS, issued a report by Flores, Bechtel, and Lowenkamp (2016) in which they argued that their algorithm was fair. Their argument is based on an idea of fairness which is sometimes called sufficiency (Corbett-Davies et al. 2017).

Here’s the intuition expressed by sufficiency. Imagine that you and your friend both received an A- in Intro CS. Suppose, however, that the instructor says different things to each of you:

- To you, the instructor says: “You did fine in this class, but I don’t think that you are prepared to take another CS course. I gave you a higher grade than I would normally because you wear cool hats in class.”

- To your friend, the instructor says: “You did fine in this class and I think you are prepared to take another CS course. Some students got a bump in their grade because they are cool-hat-wearers, but you didn’t get that benefit.”

Feels unfair, right? The instructor is saying that what a grade means for you in terms of your future success depends on your identity group.

Suppose that you heard this, but instead of cool hats it was because you are a member of an identity group that “needs some help” in order to achieve equitable representation in your chosen major. How would you feel? Would that feel fair to you?

These moral intuitions underly the principle of sufficiency as a competing idea of fairness:

A necessary condition for an automated decision system to be (approximately) fair is that, for each predicted outcome, the likelihood of the actual outcome is (approximately) equal across identity groups.

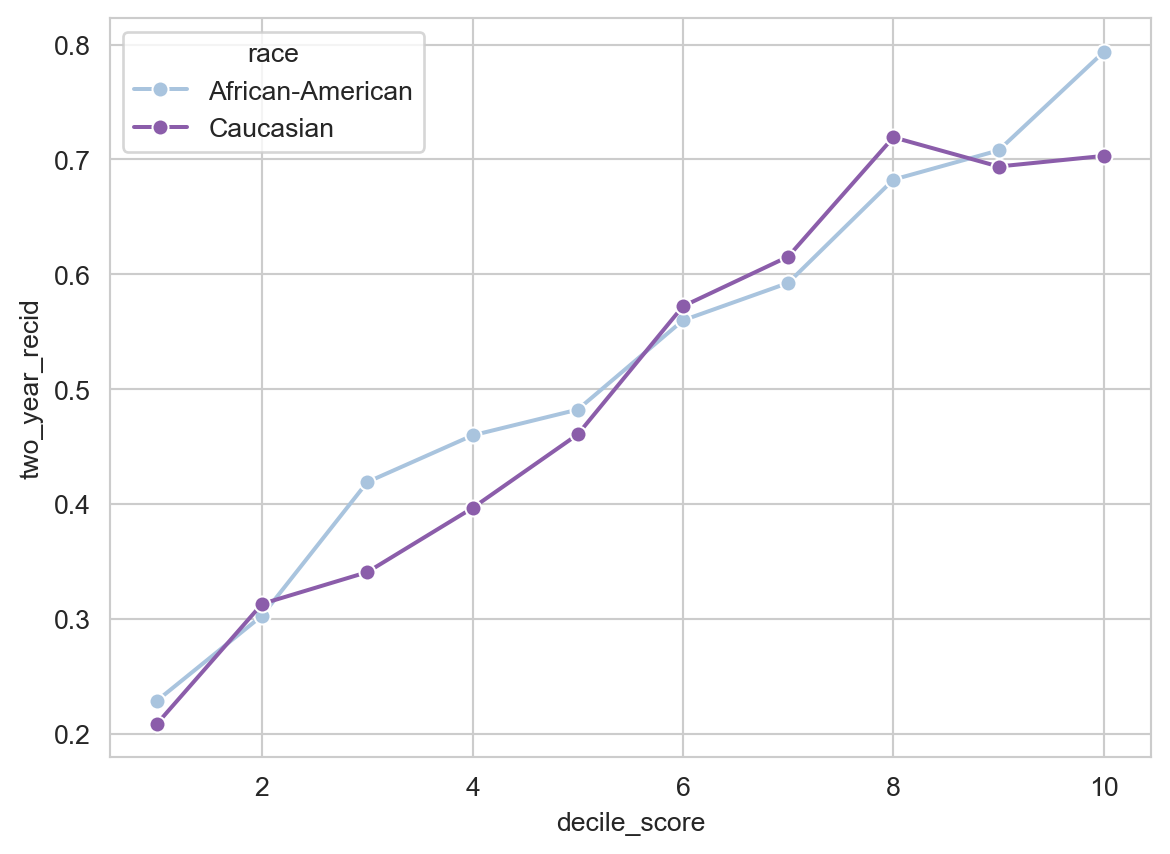

The idea of sufficiency is that a positive prediction should imply the same probability of future recidivism, regardless of racial group membership. To operationalize this idea, we can look at the recidivism rates among defendants who received each decile score, broken down by race:

scores = compas.groupby(["decile_score", "race"])["two_year_recid"].mean().reset_index()

sns.lineplot(data = scores,

x = "decile_score",

y = "two_year_recid",

hue = "race",

marker = "o",

palette = "BuPu")

The recidivism rates are relatively similar between the groups of Black and white defendants who receive a given decile score. Indeed, the decile scores with the largest racial gaps are the ones in which Black defendants have a higher recidivism rate than white defendants. This gestures towards an opposite conclusion of the one reached by ProPublica: if our idea of fairness is expressed in the idea of sufficiency, then the COMPAS algorithm may even be slightly too harsh on white defendants relative to Black defendants. Literature on this topic has generally considered the recidivism rates within each decile score to be sufficiently similar to each other that the COMPAS algorithm can be said to roughly satisfy the principle of sufficiency.

Indeed, in a rejoinder article published by affiliates of the company Northpointe which produced COMPAS, the fact that COMPAS satisfies sufficiency is one of the primary arguments (Flores, Bechtel, and Lowenkamp 2016).

Recap

In these notes, we replicated the data analysis of Angwin et al. (2022), finding that the COMPAS algorithm has disparate error rates between Black and white defendants. We introduced the idea that fairness actually has several different facets in our moral intuitions, and found that the COMPAS algorithm satisfies one of them (sufficiency: equal scores mean the same thing regardless of your group membership) but not the others (equal prediction rates and equal error rates).

Some Questions Moving Forward

- Can we have it all? Could we modify the COMPAS algorithm in such a way that it satisfies all the ideas of fairness that we discussed above? Could we then call it “fair” or “unbiased?”

- Are there other ways to define fairness? Which ones are most compelling to us? Does the right idea of fairness depend on the context in which we apply it?

- How did this happen? The COMPAS algorithm was never trained on race data about the defendant. How did it happen that this algorithm nevertheless made recommendations at different rates across groups?

- Is automated decision-making legitimate in this setting? Can it be legitimate (just, fair) to use an automated decision-system for making recommendations about parole and sentencing decisions at all? What safeguards and forms of recourse are necessary for the legitimate use of automated decision-making in criminal justice?

- What are the systemic impacts? Disparate sentencing decisions can have downstream impacts on communities and institutions. How could application of the COMPAS algorithm exacerbate systemic inequalities?